|

Automatic transmissions tend to last better than manuals, but they can and do wear out and fail. When they do, specialized knowledge is required to overhaul and rebuild virtually all automatic gearboxes.

Early automatic transmissions had two, three, or four forward gears, but the majority of automatics from 1960 to about 1980 standardized on three speeds. The first automatic transmission sold widely in America was developed by GM in the 1930s and came to market with the 1940 Oldsmobile Hydramatic. Chrysler and Ford soon brought out their own automatics, and by the late 1940s, automatic transmissions were commonly available.

During the 1950s, the automatic transmission eclipsed the manual and became the overwhelming standard on domestic cars. Foreign manufacturers came to the automatic later, but as the US market became less and less able to drive manual-shift cars, they too had to offer an automatic or accept a far smaller market.

Automatics can get by with fewer gears than manuals because their torque converters allow more slip than a clutch. As engine speed increases, the torque converter transfers more momentum to the transmission, bringing the car’s speed up. Because a clutch is a solid link between the engine and transmission, a manual transmission requires gears spaced closer together to achieve good performance. A manual transmission that slipped as much as an automatic would soon burn up its clutch.

Torque Converters

Although early automatics (such as the Oldsmobile) used different designs for the initial fluid coupling, virtually all automatics since the 1960s use a torque converter as the initial clutch mechanism. A torque converter is attached on one side to the engine and on the other side to the transmission. Inside, a torque converter has two turbine fans, like propellers facing each other, and the unit is filled with transmission fluid. The input turbine is connected to the engine and the output turbine is connected to the transmission. When the engine side of the converter begins to spin, the turbine moves the fluid around in the converter. Hydraulic motion forces the transmission turbine to spin as well, passing power to the gearbox. There’s more that happens inside a torque converter than is covered in this simple description, but the important thing to know about torque converters is that amateurs cannot work on them. They are typically purchased ready for use and delivered to rebuilders as cores when they are worn out.

How an Automatic Transmission Works

After the torque converter has brought rotation into the transmission, the motion is used to drive the transmission’s mainshaft and to operate a pump that circulates transmission fluid through a valve body. The amount of pressure coming through the valve body is governed by engine speed and the car’s traveling speed as measured by the output shaft of the transmission. By varying pressures, the automatic transmission will select the best gear for car and engine speed. Most older automatic transmissions designed for use with a carbureted engine use a “kick-down” cable attached to the throttle to effect an instant downshift when the accelerator pedal is pressed to the floor.

The actual gears in an automatic transmission are “planetary” gears. Simply put, the design works like this: an annular ring gear with teeth facing the interior rotates with the engine speed. An output shaft holds “planet” gears that can rotate around the inside face of the ring gear, turning the output shaft. At the center of the planet gears, the “sun” gear is connected to the drum. The drum is allowed to spin freely, or it can be held motionless by friction bands. When the drum spins freely, no force is transmitted, but when the drum is held motionless, the planetary gears are driven around the sun gear and pass their momentum to the output shaft.

Various gear ratios are obtained by changing the size and number of teeth on the ring, planet, and sun gears. When the valve body tightens or releases different friction bands along a row of gears, different planetary gearsets are selected with their respective drive ratios. This is why an automatic transmission can shift quickly and smoothly. As one band tightens and another is released, the engine’s torque is taken up by different set of planetary gears that is already rotating at about the correct speed.

Restoring Your Automatic Transmission

Automatic transmissions require restoration not only of bearings, bushings, and seals, but also of the friction bands and clutches and sometimes the various pressure or vacuum modulators and the valve body itself. The torque converter is usually replaced as well. Anyone performing a serious restoration should also refresh or replace the kick-down cable, gear selector connections, and any hydraulic lines leading to the transmission cooler (if installed.)

|

|

DO |

- Let your automatic transmission do its job. Don’t do too much manual gear selecting unless your transmission and gear selector is built for it

- If a transmission leaks, repair it. Do not use stop-leak additives. All the lip seals and other seals inside the transmission are made of the same material, and the stop-leak products degrade the seals

- Make sure the entire transmission gear selector linkages and kick-down linkages are in good condition and adjusted properly

|

|

DON’T |

- Don’t abuse your torque converter by revving up your engine while holding down the brake

- Don’t abuse your gears by revving up the engine in neutral and dropping the car into gear

- Don’t tow your car with the transmission connected to the drive wheels. Automatic transmissions may not pump fluid properly to lubricate the moving parts if the motive force is coming backwards through the system.

|

|

|

The Popular Restorations feature car has a three-speed, manual, overdrive transmission so there is not much to say regarding it and automatic transmissions specifically.

Packard’s first automatic transmission, the Ultramatic, came to market in 1949, but in 1946, you had your choice of a three-speed transmission with or without overdrive.

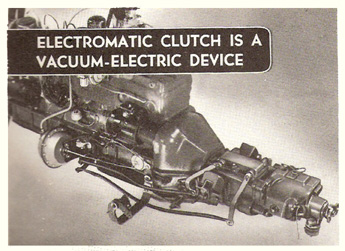

Although the Popular Restorations feature car did not come with this option, Packard offered an Electromatic Clutch which worked in conjunction with the overdrive and was identifiable by a red clutch pedal. Here’s Packard’s description from a 1941 advertisement titled, “Cut your footwork in half! Packard Electromatic Clutch!”

The Packard Electromatic clutch takes over the clutch operation...the letting-out and letting-in that used to keep your left foot so busy. This moderately priced Packard optional feature has none of the defects that marred earlier self-operating clutches. It engages at just the right rate, neither too slow nor too fast. A combination of electrical and vacuum controls does a smoother job of operating the clutch than you would do for yourself.

In another campaign, a woman was shown in a 1941 Packard with no left door with her left foot on the running board. On the car were signs, “Packard Electromatic Clutch” and “Let your left foot loaf!”

Despite the hyperbole, the system was generally thought to be too unstable to be practical, especially when the engine was warming up.

|

|

Clay Allen, Owner of Clay’s Transmissions

37765 SE Trubel Rd

Sandy, OR 97055.

503-668-4077

Clay’s transmissions in Sandy is known for its excellent drag racing transmissions, but Clay also does restoration work on all generations of automatic transmissions. Whether it’s the transmission body itself or the torque converter, Clay’s is a leading source of quality rebuilt transmissions.

PR: How does someone determine if an automatic transmission needs work?

CA: There are some inspections you can do to determine if the transmission is rebuildable. One, you can drop the pan and have a look at the contents of the pan, and that will tell you a lot. Look for evidence of clutch material or metal filings. An experienced transmission builder can read the contents of the pan and tell you a lot. If there’s nothing in the pan, you can pop a new filter on it and try and use it.

If it’s something really old, like a Dynaflow, chances are that it’s tuckered out. But it depends on the car. If you don’t know, the only way to be sure is to pull it apart and rebuild it. But people have to be aware that the early automatic transmissions from the 1950s and older, prices are at a premium. They’re not cheap.

PR: What should someone expect to pay for a rebuild?

CA: Depends on what you’ve got. If you’re working on a Dynaflow, you could run up a bill of a couple thousand dollars real easy. Not because they’re complex, but because of the cost of parts. We rely on New Old Stock parts and those are getting harder to find all the time. It depends on how obscure the unit is.

Turboglides, for example, are a real oddity any more. And the ‘55 to ’57 Chevys that are so popular to restore had two transmissions. They had a cast iron PowerGlide, which was more common, or they had a TurboGlide. The TurboGlides were kind of troublesome, mainly because people didn’t know how to drive them. So they’d get retrofitted with a PowerGlide, but if you’ve got an original TurboGlide there’s some intrinsic value to it.

PR: What goes into a transmission restoration?

CA: Starting with the torque converter, the rebuild process depends on the style. Starting back in the early 60s, most of them were a welded, sealed unit. We use torque converter vendors for that. But before the early 60s, most torque converters were bolted together, so the transmission rebuilder would disassemble the converter and overhaul it. The one big O-ring is in the overhaul kit, and he’s got to figure out if the sprags and bushings need replacement. Some of that stuff is hard to come by.

In the main transmission body, we do a complete disassembly and we examine all the sub-assemblies. We replace all the bushings, clutches and seals, and the bearings as needed.

PR: Can an amateur do this work in a home shop?

CA: Again, it depends on the unit. A real mechanically-inclined and savvy kind of fellow who takes his time and has a well-written manual can overhaul an older automatic transmission.

PR: Is it a good idea to buy a transmission from budget advertising papers and websites?

CA: You have to be really careful about that. There’s an awful lot of crap out there. From what I see coming into my shop, some places tear a bunch of transmissions down and they build transmissions out of barely usable parts. It’s a “buyer beware” kind of thing. Doing a good job takes time and takes parts, and it costs money.

PR: What’s the difference between Dexron and Type F Automatic Transmission Fluids? Is it safe to use either kind of fluid?

CA: In the old days they used some other designations. But the modern fluids retrofit into the older units just fine. When I work on the older Ford transmissions that used Type F, I use Dexron. You can put Dexron in any transmission and it works just great. It’s an old wive’s tale that you can’t mix the two. It’s all baloney. Dexron retrofits just fine, and may even work a bit better.

The difference is that Type F has no friction modifier in it, but Dexron has always had some kind of friction modifier additives for smoother engagements and better clutch application. Over the years they’ve revised that several times until you get to the modern versions. Ford hasn’t used Type F since 1977.

|

| Click on any item below for more details at Amazon.com |

|

|

|

Eric Godfrey, John Harold Haynes

The Haynes General Motors Automatic Transmission Overhaul Manual

Haynes Publications, Paperback, 1996-04 |

|

If you’ve got a GM automatic transmission, this is the book. It may well be the only book not published by the factory. Covers all aspects of rebuilding all commonly-available GM auto transmissions of the 1960s and 1970s - THM200-4R, THM350, THM400, THM700-R4.

|

|

Max Ellery

Transmission Repair Book Ford 1960 to 2007: Automatic and Manual

Max Ellery Publications, Paperback, 2003-05-01 |

|

This book has step-by-step instructions for a pull down and rebuild. Includes specifications, torque settings, problem diagnosis, shift speeds plus more information. This book is from an Australian publisher, and covers both American and Australian applications.

|

|

Carl Munroe

How to Rebuild or Modify Chevrolet’s Powerglide for all Applications

HP Trade, Paperback, 2001-05-01 |

|

This well-reviewed book as step-by-step instructions on how to modify the General Motors Powerglide Transmission for drag racing, road racing, and circle track racing. Includes sections on theory of operation, transbrakes, valvebodies, adapters, disassembly, modifications, assembly, adjustments, installation, high horsepower applications, and torque converters.

|

|

Ron Sessions

How to Work with and Modify the Turbo Hydra-Matic 400 Transmission

Motorbooks, Paperback, 1987-12-31 |

|

This book is presented in a how-to format and combines step-by-step instructions with 450 photos, detailed drawings, tool lists and charts. Chapter content includes basic maintenance, automatic transmission theory, removal, rebuilding, installing, final checks, parts interchange, and break-in pointers.

|

|

J. Gary Campbell

Automatic Transaxles and Transmissions

Prentice Hall, Paperback, 1998-04-07 |

|

This text presents a wide overview of the operation of automatic transmissions and transaxles. It provides the fundamental knowledge an automotive student needs to become an entry level automatic transmission and transaxle technician. Covers operation, diagnosis, and repair.

|

|

|

|