|

Most restoration projects involve some attention to a car’s transmission, although it’s far more common to find a transmission in good condition than to find a good engine or brakes. For most of automotive history, three speed manual transmissions were the norm. Then four speeds came along, followed by five and now six speeds in modern cars. But the vast majority of manual transmission restorers will be looking at three or four forward gears.

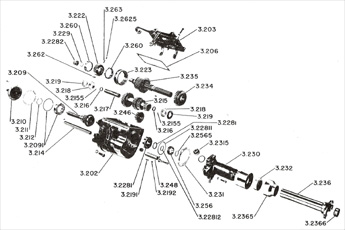

The basic design of a manual transmission is relatively simple. Your engine transmits rotational motion through the crankshaft, flywheel, and clutch to an input (AKA ‘first motion’) shaft that brings the rotational momentum into the transmission. Inside the gearbox, that rotating input shaft is connected to one of several reduction gears, or straight through to the output shaft. The output shaft is connected to your differential, drive axle and wheels.

In practice, the inside of a transmission is a very precise and complex assembly, especially if your transmission includes synchronizers to help you shift gears smoothly. Transmission restoration is generally a job for a professional.

Part of the complexity of a manual transmission lies in the mechanism that allows the driver to select gears. Moving the gear selector on the cabin’s floor or mounted on the steering column actuates a series of rods (or sometimes cables) that slide collars or forks back and forth within the transmission. These collars or forks hold splined gears that engage the selected drive gears to the input and output shafts.

One reason a transmission must be precisely assembled is that as the driver moves the gear selector, it is critical that the shift fork motion disengages the previous gear before engaging the next.

Synchro vs. Crashbox

Modern transmissions use synchronizers to encourage the input shaft and the selected gear to spin at the same speed as the driver moves the gear selector into position. There are several designs but for vintage transmissions the most common synchronizer is a cone-shaped clutch. The benefit of a synchronized gear is that smooth shifts are possible with less skill and finesse--synchronizers allow most people to successfully drive a manual transmission car.

Many older transmissions are unsynchronized. This means that the driver must alter the engine speed to match the revolution speed of the gears in the transmission before shifting gears. Unsynchronized transmissions are often called “crashbox” trannies because of the horrifying sound they make when shifted incorrectly.

Many transmissions made well into the 1970s used synchronizers on all forward gears except first gear. For these cars, it is good practice to come to a complete stop before attempting to engage first gear. Almost all transmissions to this day use an unsynchronized reverse gear. Exceptions include some exotic cars such as Lamborghini Diablos and some modern Volvo models.

Shifting into Overdrive

All modern transmissions and many older gearboxes include at least one overdrive gear--defined as a gear ratio less than 1:1 (generally expressed as 1.000). Generally these overdrive gears are about the same ratio--somewhere about 0.7 or 0.8 to 1. At the other end, most first gears are about 3.5:1. Automatics typically have taller first gears, up to about 2.7:1, because their torque converters allow more slip than a clutch.

Restoring Your Transmission

There are several critical areas to restore in a transmission. If you have synchronizers, these are the most important hard parts to replace to get “like new” shifting from your gearbox. Also, check the main gear set. Many gears are case-hardened and this hardening is a thin layer on the surface of the metal. When this hardened layer wears through, your gears will wear down rapidly. Bearings and bushings also wear as the transmission shafts turn, and often need replacement. Finally, make sure your transmission rebuilder uses a new set of gaskets and seals to keep your transmission oil inside the gearbox where it belongs.

|

|

DO |

- Shift your transmission smoothly, allowing time for the synchronizers to do their job, if you have them

- Have your transmission rebuilt by a professional. Trying to save a relatively small amount of money without the specialized knowledge necessary to evaluate and repair a complex transmission is false economy

- Ensure that your transmission is filled with the correct lubricant

|

|

DON’T |

- Don’t try to shift your car faster or harder than it was designed to take

- Don’t shift your car without using the clutch

- Don’t “bump-start” your car if you can avoid it

- Don’t tow your car with the transmission connected to the drive wheels. The gears will not be lubricated properly.

|

|

|

As I drove the Popular Restorations feature car from Sacramento, California to Portland, Oregon I noticed it had three transmission problems: the synchromesh was gone when shifting into second gear, it would pop out of first gear when decelerating, and it wouldn’t shift into overdrive.

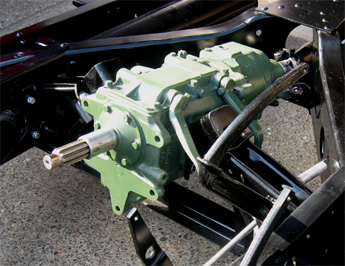

I planned on doing the rebuild myself. I had rebuilt three-speed transmissions before, so wasn’t too intimidated by the Packard’s overdrive unit. But, as the time drew near I figured I’d save a lot of time having a professional do it. The transmission was out of the car but I didn’t want to make a mistake and pull it out again. Removing the Packard Seven Passenger transmission is not as easy as dropping a 40s Chevy, Plymouth, or Ford. It has two cross-members that have to come out, a split drive shaft that goes through an X-brace, and the transmission weighs a ton.

I had already purchased the rebuild kit from Kanter Auto Products, so I took the transmission to a reputable shop. The price was around $600, which wasn’t bad, but when I started the car I was immediately disappointed. The front bearing made noise when the clutch was out (in neutral). Packards are supposed to be so quiet you can’t tell if they are running when idling. I took it back to the shop and the mechanic said some older transmissions are a little noisier than others, so that wasn’t much help. To make matters worse, when I hooked up the overdrive it would grind when trying to shift.

I felt like I was partially responsible for the front bearing. After all, I was the one who bought the rebuild kit. And I don’t know if the shop actually worked on the overdrive--I hadn’t asked them to fix it, assuming it was an electrical problem. I asked around at my car club and one of the senior members recommended Transmission Exchange in Portland. They have an older manager who oversees work on classic car transmissions. So, I bought a Harbor Freight transmission jack and pulled the thing out in a couple of hours. Transmission Exchange said the front bearing seemed fine but that it was a Chinese bearing so they replaced it. They also said the overdrive had been assembled improperly and they corrected that. Six hours of labor and 500 dollars later the transmission was in the car and working well. I guess it was all worth it but it was certainly frustrating along the way!

|

|

Bruce Murray, Owner

3411 SE Milwaukie Ave.

Portland, OR 97202

(503) 235-9821

Majhor & Murray is one of the leading rebuilders of vintage transmissions in the Portland area, and they have seen thousands of domestic and imported transmissions over the years. We asked the owner, Bruce Murray, to sit with us and talk about the restoration process.

PR: What goes into the transmission restoration process?

BM: The first thing we do is disassemble it to see what it needs. As we disassemble it, the parts go into a hot tank to be cleaned. Then we can do some inspection. On an old gearbox, we’ll use all new bearings, and any damaged gear teeth, synchronizers or speed gears will be replaced.

PR: What’s a speed gear?

BM: A speed gear locks the transmission in compression. It keeps the car from popping out of gear when you release the throttle. If the speed gear is good and the teeth are good, you can use it again. Most restored cars won’t be driven 40,000 miles per year - they may be driven only 2,000 miles per year, so you have to use some common sense about replacing things. It’s easy to spend money when it’s not your money, but we want to have a satisfied customer with a good piece in his hands.

PR: OK, so what happens next?

BM: After the inspection, we secure the parts that are required. That’s not always easy. We have a good resource here in Portland for a lot of New Old Stock pieces. They have warehouses in Portland, Oklahoma, and Kansas. So if I need a second speed gear with 16 teeth for a Borg-Warner T-85 1957 Ford heavy duty three-speed transmission. That gear might not be in Portland, but they’ve got two in Kansas and a good used gear in Oklahoma. Unless the customer wants all new parts, we’ll order the used part and save some money. Sometimes these pieces come in a week, and sometimes it’s three to five to seven weeks. Bearings are normally not a problem.

PR: How about the outside?

BM: When we finish a transmission, we paint it according to the customer’s request. A lot of Ford guys want the transmission painted in Ford Green for a 1935 through 1939. From 1941 through 1948, it was a little different color. But if it’s a real resto, they want it painted like it was when Henry built the car.

PR: How much should someone expect to pay for a good transmission rebuild?

BM: That depends on the type of transmission. If it’s a 1939 Ford transmission, which is a synchronized 3-speed. That is, low gear is not synchronized, but second and third gears are. That box, when finished, is generally worth between $550 and $900. They’re not terribly expensive. But you can also take a Muncie 4-speed transmission and get $1100 to $1300 into it. They have notoriously bad cases, and they leak oil from years of abuse. A lot depends on what the customer is doing. If they’re going to show the car, it’s important to get the right numbers-matching parts. For muscle cars, that’s extremely important. For a 1948 Nash, on the other hand, the next guy wouldn’t know what it was as long as it was a 1948 Nash transmission.

PR: If I buy an unrestored car, how do I know if I need a transmission rebuild?

BM: If someone brings me a transmission, I pull it down and take a look at it. If it’s not all busted up, we use common sense and say “this will run your car for years.” Sometimes we can just tell someone that he can keep using a gearbox with just a new set of seals and gaskets. Then the guy says “thanks a million” and he’s only into it for a couple hundred bucks. But on the other hand, sometimes they’re so bad they can’t be rebuilt, so then I can go source another one through my connections that I’ve built up over the years.

|

| Click on any item below for more details at Amazon.com |

|

|

|

Robert Bowen

How to Rebuild and Modify Your Manual Transmission

Motorbooks, Paperback, 2005-11-10 |

|

This book explains how to rebuild and modify transmissions for rear and front-wheel-drive cars. It includes how to determine what parts to replace; how and why to replace certain seals, spacers, springs, forks, and other parts; and where to find (and how to measure) the specifications for each particular transmission.

|

|

Jack Erjavec

Today’s Technician: Automotive Manual Transmissions & Transaxles

Delmar Pub, Paperback, 1997-01-14 |

|

This is a set of books. The classroom manuals provides the necessary theory to understand manual transmissions while the shop manual provides the hands-on experience. It includes sections on the basics of electricity and electronics as it relates to drive train systems, six-speed transmissions, new differential gearing, inertia flywheel systems, shift blocking, and 4-wheel drive and all-wheel drive systems.

|

|

|

ProCarCare.com has a good article titled Clutch and Manual Transmission/Transaxle.

CarBibles.com also has a good article titled The Transmission Bible.

|

|

|